The new Prado Museum website: A (semantic) challenge

Javier Pantoja, Museo Nacional del Prado, Spain, Javier Docampo, Museo Nacional del Prado, Spain, Ana Martín, Museo Nacional del Prado, Spain, Ricardo Alonso Maturana, GNOSS, Spain, Carlos Navalón, cnc studio digital, Spain

Abstract

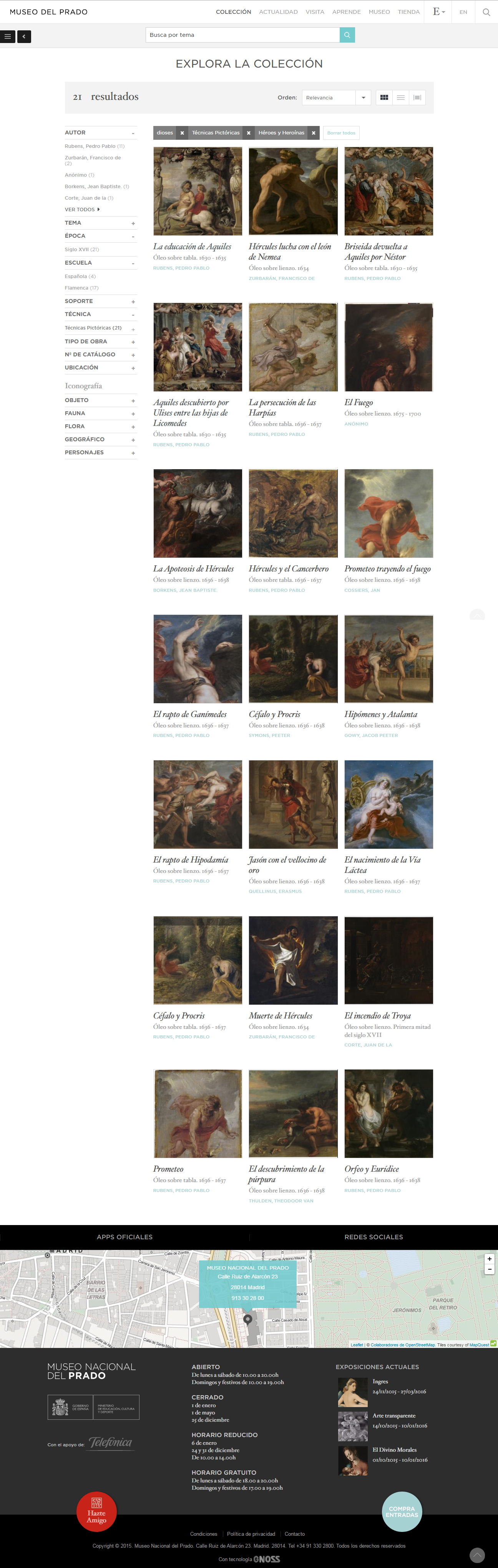

Two years ago, the Prado website was reaching the end of its useful life. Since its launch in 2007, it had become the reference and main access to Prado’s information for the general public. Prado’s most important asset is the Collection, and this was the axis of the new website project. The Collection would be the center. Besides, after several changes in the Internet paradigm, the Prado needed a new website with new features, including the basic checklist of a modern website: responsive design, markup language, greater integration with social networks, broadcasting multimedia content, etc. But the key point and most relevant feature of the project was that the Prado’s new website was going to be based on the principles of semantic web, a structured data website that would shift the use of the Collection's documentation. It required the creation of a digital semantic model defined by a methodology based on different ontological standards. The final proposal was a faceted search engine at the service of the general public that would be able to explore the Collection in many different and new ways. The aim was to generate contexts and other recommendation systems with internal and external content. For the near future, our aim is to bring value to each other's content by interconnecting our Museum’s document database with other museums and cultural institutions as part of the Linked Open Data Project.Keywords: website, UX, faceted search, semantic model, CIDOC-CRM

1. Strategic plan: The commission

In 2013, the Museo Nacional del Prado published its 2013–2016 Action Plan. This plan defines the museum’s general strategy and is proposed by the institution’s Management for approval by the Royal Board of Trustees. The plan contains five programs for activities, the fifth of which—Prado Online—will be addressed herein. Prado Online pursues the following strategic objectives:

- Increasing knowledge of the museum’s collection and activities via the Internet

- Optimizing and facilitating online access to content and information about the museum, regardless of location, device, or access platform

- Creating community through social networks participating in current dialog about art and museums

Three fundamental activities were considered necessary to meet these objectives: Prado Website, Prado Mobile, and Prado Social Networks. While all three are related to the Museo del Prado’s new website project, Prado Website merits the most attention, as the museum’s previous website, launched in 2007, had met its goals but was no longer considered viable. Prado Website was intended to increase access, usefulness, visibility, and knowledge of the Museo Nacional del Prado’s collection, and to present contents related with the museum’s general activity via its website. To do so, it was considered necessary to carry out the following activities over a three-year period:

- Completely redesign the Museo del Prado’s website, with special emphasis on a better and more user friendly navigating experience

- Expand website contents to cover all of the museum’s educational, scientific, and research activities

- Restructure information with a new architecture of contents

- Develop new functions and applications that offer users direct and participative online interaction with the website and its contents

- Update website technology at the level of code and content management, as well as its hosting infrastructure and connectivity

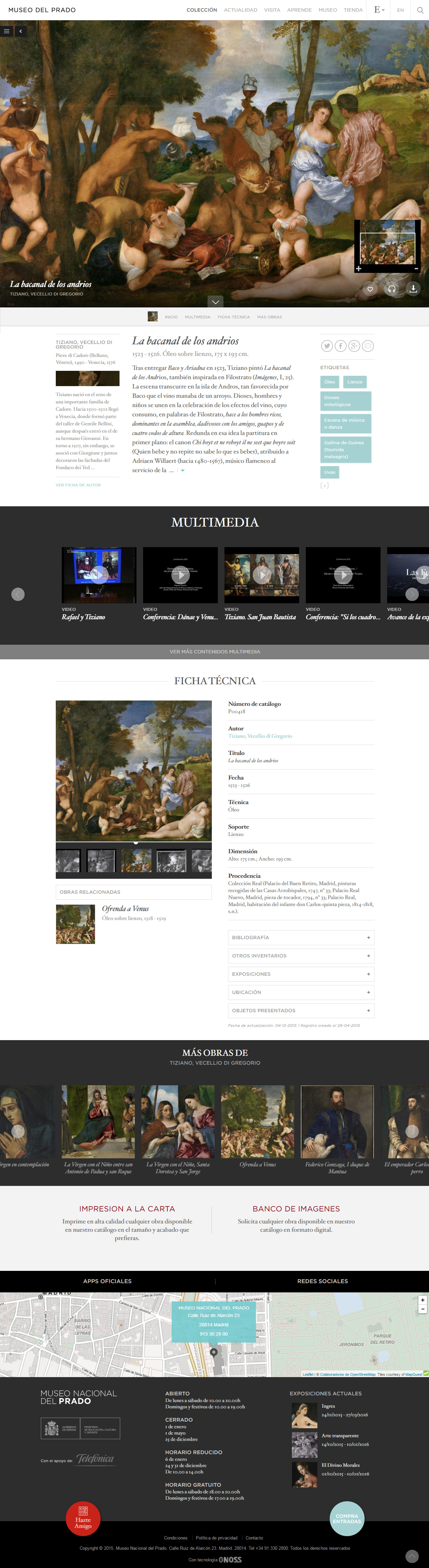

- Include entries for the artworks that make up the museum’s collection, each of which offers: complete technical data on the work, bibliography, technical documentation regarding exhibitions and provenance, etc.

- Inclusion, unification, and interrelation in the website of the museum’s internal documentary knowledge bases to provide user access to them

- Semantization of the included knowledge bases and of the new website’s main channels by applying to the new website semantic technologies associated with the search and recovery of information about the collections

- Generation of contexts for contents that favor interoperability with the institution’s different knowledge bases, as well as with other museum and cultural institutions via their corresponding websites

- Linking the museum’s documentary knowledge bases with spaces of the Linked Open Data Web so that they can appear in other contexts focused on education, research, etc.

- Progressively opening data contained in the different knowledge bases and their reuse by third parties (OpenData)

Coordination of this project was assigned to the Web Department of the Communications Area belonging to the museum’s Management division. During these years, the Department’s mission has been to direct the project, which involved various questions:

- On an internal level, coordinating different museum departments and serving as an interface between those focused on technological matters and those focused more on content

- On an external level, contracting and dealing directly with professionals and outside companies in their relations with the museum’s different departments

The project was organized in three parallel and interrelated phases:

- Updating and adaptation of the Integrated Document Management System coordinated by the Documentation Department and the IT Department with the coordination of the Web Department as the basis for the project

- UX analysis, key ideas, design concept, structuring of contents, prototyping, navigation and usability, and formatting of the front end carried out by an outside UX and design team (CNC Designers), along with the Museo del Prado’s Web Department

- Semantization of the documentary knowledge bases, Structured Data Web, and Semantic CMS carried out by an outside company, Gnoss, our technological partner

2. Integrated document management system: Material and support

Information about their respective collections has become a leading asset for all museums, not only for generating a greater flow of visitors to their galleries, but also to situate them as institutions capable of generating scientific knowledge and making it available to all citizens. In order to make this visible online, the first step was to gather and structure data about the collections, and the second was to keep it up to date, which requires the museum to continuously offer new information to users via the Web.

The Museo del Prado has been working over the last ten years to make this a reality. Its Documentation Department, belonging to the Library, Archives and Documentation Area of the Deputy Director for Collections and Research, has been involved in launching an integrated document management system (SIGMA) based on knowledge bases belonging to the different museum departments that work with the collections. The key idea underlying this entire process is not only to link these knowledge bases but also to transform all of the museum’s internal work processes into relevant information about the works.

This document system could not remain sequestered for the exclusive use of the museum’s technical personnel. From the very start, it had to constitute the museum’s main communications channel for the enormous amount of information about this institution’s artworks. At first, it was made available via terminals in the museum library’s reading room, but it soon became clear that this system should become the main source for presenting the collection on the museum’s website.

Today, this management system automatically gathers information supplied by each of the museum’s departments, which allows it to be permanently up to date. This required previous agreement as to what data should be for internal use and what part of its management could generate information whose relevance would make it worthy of public access. This process required the museum’s IT Department to create a relational knowledge base in SQL for hosting the data, as well as a system for updating, loading contents, and consultation based on Boolean search protocols and hierarchical and relational tables. The entire process was coordinated by the Documentation Department, which gathers, processes, and filters data for publication.

The essential core of the information about the museum’s collections consists of the basic information that allows each work to be correctly identified: number, author, title, technique, support, dimensions, date, school, type of object, subject, objects represented, and provenance. Of these, title and provenance are free-text fields; the rest of the data is entered through hierarchical tables created ex profeso on the basis of the main thesauruses and vocabularies of artistic heritage. The Web exportation of all these tables required a double adaptation process. First it was necessary to determine what level of the hierarchical table had to be shown in order to generate relevant search results. Second, all of those tables had to be translated into English, so that they would function in English-language searches in the English version of the website.

The management system includes not only textual data about the collection, but also images. These are the responsibility of the museum’s Photographic Archives, which depends on the Artworks Registry Department. Beginning with a manual system for linking images to the entries on each artwork, this link has been achieved in an automatic manner, which allows daily updating of any work’s main image. Moreover, the system offers the capacity to select more than one image, allowing simultaneous contemplation of details, X-ray images, etc.

The location of artworks is handled by the Registry Department and is also updated automatically. Locations exported to the website are defined as: exhibited, on deposit, or in a temporary exhibition. The rest of the locations are categorized on the Web as “not exhibited.” Information about exhibitions in which works have appeared is handled in a similar manner, on the basis of data from the temporary exhibitions management program. Accessible information includes the title of the exhibition, its date, and location. Also, if there is already a specific micro-site on the website for that exhibition, the corresponding link is established.

Not all information is automatically updated. The Documentation Department works on the inclusion of each work’s bibliographical and documentary references, linking the corresponding registers with the Library and Archives’ knowledge bases, each of which has been developed with commercial software. The presentation of the bibliography on the website called for cleaning available data, much of which had been entered years ago, before the Library had normalized its cataloging.

To recognize the scientific authorship of the museum’s professionals, the Documentation Department chose to indicate the sources of catalog data and commentaries on the art works. This solution has facilitated the constant flow of information between the internal knowledge base of the collections and the website.

3. The digital experience: Subject and composition

Aware that it is impossible to match the visitor’s sensations in the actual presence of a masterpiece, our aspiration has always been to create a new digital experience in which the online visitor can also feel emotions. Consequently, a digital experience of the Prado had to be worthy of such an institution, and it had to meet all such expectations. From the standpoint of UX (user experience), the project sought to bring this strategic thinking into the field of experience. The new Web should not be just a digital department, website, or app; it had to become an essential part of the Prado, a digital extension of the physical museum, capable of establishing a new digital relation with the visitor. To achieve this, we decided to bring the experience of a physical visit to the museum into an enriched digital setting, thus redefining the user’s experience.

We began the project with an understanding and definition phase, applying certain analytical tools available to UX professionals. The first technique was ethnographic analysis, which was used to study the behavior of visitors inside the museum—always attempting to avoid interfering with their actions, uses and habits. We observed their manner of approaching and contemplating artworks and how they bought tickets, consulted guides, and listened to audio tours. Beyond this passive observation, we carried out direct mini-surveys with specific types of visitors.

This technique, along with other forms of data gathering, helped us gain greater knowledge of physical visitors. Still, what we most needed to identify were the needs, expectations, and barriers faced by the Prado’s digital visitors. To do so, we used another UX technique created by Alan Cooper: the creation of persons (Cooper, 1999). The main goal of this technique is to grasp the mental model of our principal target demography so that the museum’s Web responds to that determined mental model.

The UX/Design team, along with the team in charge of developing the museum’s project, defined up to fifteen profiles of personal archetypes—from a secondary school teacher to an American family, from housewife to student—recreating detailed personalities on the level of user profiles in order to more precisely describe the Web’s target and make design decisions easier. We discovered one element shared by all of the main personas defined in this way: a “cultural snacking behavior” that reflected an interest in culture without the need to be an expert. In order to engage digital visitors, our goal was to design in response to that kind of behavior. We found elements shared with the archetype defined some years earlier for the development of the Rijksmuseum’s new website (Gorgels, 2013). Thus, the objective of the museum’s new digital experience is to satisfy the curiosity of “cultural snackers.”

To define the information architecture and navigation design for the Prado’s new website, we considered the following three elements:

- Analysis of the content and structure of the museum’s previous website. We discovered that most of the content was overly compartmentalized, like a writing desk with thousands of drawers containing, but hiding, tons of valuable information.

- The use of data-structuring systems based on semantic ontology, in which all content would be interrelated.

- Statistical analysis of use of the Prado’s website, which the museum provided us via Google Analytics, showed that most searches were organic, and that there was a continual increase in direct access from social networks, especially Facebook and Twitter, in which we appreciated a sustained real growth of visits.

On the basis of this data, we decided to define the new information architecture through a much simpler and more accessible structure with only six main areas, two transversal options, and a powerful search engine. This insured the transition from a writing desk with a thousand drawers to a desktop with only one.

With respect to the design of the new website’s navigation, we created an interactive model that assigned a greater role to entries with independent relational modules, making it possible to navigate from the content, from one work to another, from the related tags or from the search engine. Content thus became navigation itself.

The entries on the Prado’s artworks connect all of the digital content and constitute the main axis of the new experience, a new digital universe of emotions in which the Prado improves its record by approaching its masterworks through multiple levels of exploration. In sum, a world of information related to the artwork in an enriched digital setting, where everything can be shared, stored, or sent. We have thus achieved a straightforward and entertaining yet deep experience aimed primarily at the “cultural snacker.” We knew from the very start that we would never be able to emulate the visitor’s experience in the presence of the original masterwork. Nonetheless, we wanted to bring the artwork closer to digital users and expand their experience of its online presence. We believe that this new website definitively casts the artwork as the true protagonist.

From the standpoint of UX/Design, the project has given us a chance to discover that, beyond designing a new digital experience, we have designed the conditions necessary for an excellent user experience. This is strategy, not design. The team in charge of design has not been the only one to define those conditions. Almost every department in the museum has become involved and participated in the creation of the Museo del Prado’s new digital experience. (http://wwww.museodelprado.es)

4. Semantics: Technique and maniera

The new website’s main objective has been to extend the direct visual experience of the artwork in the Museo del Prado to the Web. For this to be possible, it was necessary to find a very clear way of offering to the public the rich group of resources and content that make up the collection in a user-friendly, straightforward, practical, intuitive, and interesting manner. To do so, the museum’s heritage has been represented in a queryable, highly expressive, and expandable unified knowledge graph.

The museum’s knowledge graph is unified because it begins by linking the artworks and authors in its collection, enriching them with other knowledge assets from this institution, such as the encyclopedia or archives. Moreover, all of this is linked to other objects of knowledge handled by the rest of the museum, such as news, exhibitions, video resources or merchandise. The knowledge graph is queryable because it offers a search engine that is presented as a faceted search tool designed to offer all museum Web visitors means of finding information compatible with their interests and intentions. The search engine allowed iterated queries, so that searches can be as specific as necessary. This enables us to present users with results that are focused and well organized by groups, as well as enriched and contextualized. In sum, it was a matter of providing users with the most intuitive, intelligent, personalized, semantically significant, and efficient navigation experience, thus encouraging them to enjoy their visit for longer periods of time.

Another goal was to foster the generation of specific websites related to temporary exhibitions or other conditions determined by the moment. The project also wanted to offer users a tool for creating, editing, and publishing itineraries, collections, and personal museum narratives that could have a recreational, informative, and educational value. This function is called My Prado. Finally, we sought to insure that this new experience would work on any sort of platform, so that all users could access the Web museum from any place at any time.

The museum also considers the future use of this sort of graph a means of facilitating the development of advanced departments for different user groups, thus enabling the institution to increase its number of registered users and, eventually, of subscribers. In sum, an effort has been made to build a more open, usable, and accessible museum, instead of simply developing a new Web page for the museum.

From an internal viewpoint, the project aspired to develop a rapid and tuned system for editing and creating contents in order to shorten the distance between the museum and the varied sectors of the population that a public institution must address, and for which it must speak. The knowledge graph is used to annotate, organize, and present museum information in a significantly relevant way—for example, by including in the entry on an artwork, all of the relevant information related to it, regardless of where that information comes from or what team generated it, as well as its relation to other works in the museum and its maker’s relation to other artists represented in the collection.

From the very start, the construction of this new online presence sought to use museum data to improve its own processes of documentation, editing, communication, and publication, rather than simply representing them in ways that could be reused by third parties. This focus has notably affected how the museum operates internally by connecting processes of knowledge creation and generation with those involving the publication and presentation of knowledge. The results of adopting this approach show that when the focus is on developing tools for different user groups, including those within the institution, it is possible to enact a digital transformation process capable of significantly changing the means of producing and consuming materials that represent the institution’s heritage and knowledge.

The Museo del Prado’s Knowledge Graph has been constructed using semantic Web standards based on the Linked Data Web principles that designate a structured method of data publishing. In practice, that is what makes it possible to navigate via hyper-data. To publish in accordance with Linked Data Web principles, it is necessary to follow certain standards, including HTTP, OWL/RDF, and URIs, which are used not so much to serve pages read by persons as to edit pages that can automatically interpret systems and thus share information with them. This allows the connection of data from different museum sources in a unified and queryable graph, which has, in turn, made it possible to:

- Connect the construction of the Museo del Prado’s rich knowledge base—generated over time through the constant efforts of its curators and cataloguers—with the publication of the Prado’s website, so that what is visible on the Web is what is being created and generated by the entire institution in its different areas of research

- Optimize the use of the knowledge base, enhancing the combined value of work by all of the institution’s areas

- Convert the current Museo del Prado’s Web of Documents into a Knowledge Graph that is expressed via a Linked Data Web

- Develop modes of querying and visualizing this Graph that respond to the needs of different groups of users, with the intention of satisfying their interests as much as possible, offering information explicitly related to those results that answer users’ questions

- Construct thematic Web pages on the basis of a group of data or sub-graph that meets certain requirements

- Provide the website editing team with news and information about authors, artworks, subjects, events, etc. related to a given work, author, exhibition, or event, thus facilitating accelerated generation of new news, activities, or general contents

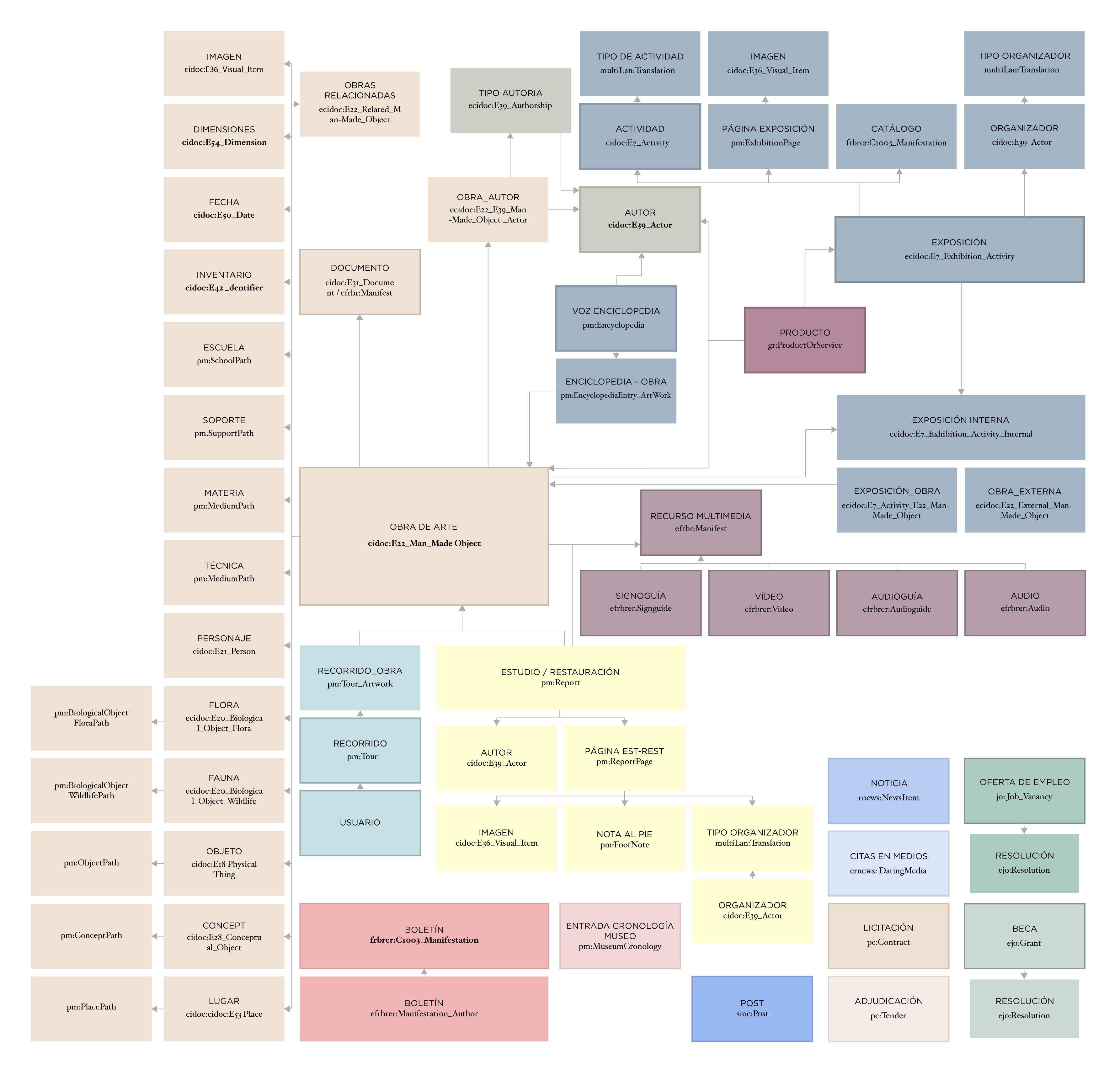

A domain ontology (or domain-specific ontology) represents concepts that belong to a specific part of a totality; but domains in which the totality of concepts are organized are usually less pure than our controlled vocabularies. That is why overall systems, of which a museum could be considered an example, need hybrid ontologies based on the combination and integration of different domain ontologies to obtain a more general representation.

The ontological project developed by the Museo del Prado for the construction of its knowledge graph hybridizes a broad group of ontology domains, integrating them into a shared framework or ontological narrative that represents the overall group of activities taking place in the museum setting; that is, the group of techniques, practices, and processes involved in a museum’s functions. These span a gamut from documentation associated with processes needed to preserve the collection to communication with the media and information about the museum’s activities and publications, along with online sales of objects from the Prado’s shop. The hybrid ontology mentioned above has taken the form of what we could call the Museo del Prado’s Digital Semantic Model, which consists of a group of vocabularies articulated around the CIDOC-CRM (Conceptual Reference Model). In practice, and with the necessary adjustments, this makes it possible to adequately represent most of the museum’s central processes.

The CIDOC CRM (http://www.cidoc-crm.org/) is a semantic model that has been evolving since 1994 and was developed by the Documentary Normalization Group of the International Committee for Documentation that pertains to the International Council of Museums (ICOM-CIDOC). In 2006, the ISO published the CIDOC CRM as an international norm (ISO 21127:2006). It consists of a semantic model that constitutes an “ontology” of information related to cultural heritage. The CIDOC model consists of a hierarchy of some ninety classes and close to one hundred and fifty properties that meaningfully connect those classes. The main entities of the Prado’s semantic Web—Artwork, Author, Exhibition, and Activity—are represented according to that CIDOC CRM standard.

The FRBR (Functional Requirements for Bibliographic Records) (http://archive.ifla.org/VII/s13/frbr/frbr_current_toc.htm) is a conceptual model developed by the International Federation of Library Associations and Institutions (IFLA). Its purpose is to establish a framework that provides a clear, precisely defined, and shared understanding of the information that a bibliographic record should offer, and most of all, what can be expected of a bibliographic record in response to user needs. The FRBR standard has been used to model all of the museum’s bibliographic records.

The project has also had to adopt other standard vocabularies and ontologies to control objects of knowledge not addressed by the previous ones, such as the rNnews ontology (http://dev.iptc.org/rNews) develop by IPTC (the International Press Telecommunications Council) as a means of representing news; the PPROC ontology that defines concepts needed to describe public bidding processes and contracts in the public sector; the Human Resources Management Ontology that sets the standard for offering employment and scholarships; and the W3C’s SIOC (Semantically Interlinked Online Communities) (http://rdfs.org/sioc/spec/) to represent content published in social spaces.

The Prado’s digital model is organized, at the upper level, around the following eighteen Objects of Knowledge: OK Artwork, OK Author; OK Exhibition; OK Encyclopedia entry; OK Event in Museum Chronology; OK Activity; OK Study/Restoration; OK Employment offer; OK Scholarship; OK News item; OK Media quote; OK Multimedia resources (video, sign-language guide, audio, audio-guide); OK Bulletin; OK Bidding; OK Adjudication; OK Social Network Post (Facebook or Twitter); OK Product; and OK Itinerary (My Prado). The Prado’s knowledge graph includes some 20,000 resources, 310,000 entities, and some 2,830,000 relations among those different objects and entities, which are used to understand the meaning of the terms that users employ in their searches. To insure greater control of the vocabulary employed in object descriptions, a specific OWL ontology has been applied to the Museo del Prado’s semantic project and to each of the mentioned objects.

5. Conclusions: A new way of working, a new perspective

The main idea underlying this project was not to create a new website, but instead to bring the experience of the Prado to the Internet. Focusing on the user in order to create a museum online and doing so in such a way that the experience become equally agreeable and interesting.

To carry out the Museo Nacional del Prado’s new website, it has been necessary to generate internal work dynamics among the different departments. This has led to a change in the institution’s mentality, which is no longer focused only on researching, documenting, and preserving its collections, but also on achieving their maximum visibility, with the Internet as a tool for doing so—one whose relevance is growing on a daily basis. This has led to the reorganization of many internal workflows, including the creation of a Digital Development Area that combines what, in previous years, has been the labor of the Web Department and the IT Department. In light of the work being done throughout the museum, a digital approach has been considered of paramount importance. The semantization of its collections opens new and very interesting paths for future work that the Prado is eager to explore in the coming years.

Acknowledgements

To all of the Museo Nacional del Prado’s staff, from the first security guard to the last director.

References

Allemang, D., & J.A. Hendler. (2008). Semantic Web for the Working Ontologist: Effective Modeling in RDFS and OWL. Oxford: Elsevier Ltd.

Cooper, A. (1999). The Inmates Are Running the Asylum: Why High Tech Products Drive Us Crazy and How to Restore the Sanity. Indianapolis, IN: Sams.

Gorgels, P. (2013). “Rijksstudio: Make Your Own Masterpiece!” In Museums and the Web 2013, N. Proctor & R. Cherry (eds.). Silver Spring, MD: Museums and the Web. Published January 28, 2013. Consulted January 28, 2016. Available http://mw2013.museumsandtheweb.com/paper/rijksstudio-make-your-own-masterpiece/

Segaran, T., C. Evans, & J. Taylor. (2009). Programming the Semantic Web. Beijing; Sebastopol, CA: O’Reilly Media.

Cite as:

Pantoja, Javier, Javier Docampo, Ana Martín, Ricardo Alonso Maturana and Carlos Navalón. "The new Prado Museum website: A (semantic) challenge." MW2016: Museums and the Web 2016. Published January 28, 2016. Consulted .

https://mw2016.museumsandtheweb.com/paper/the-new-prado-museum-website-a-semantic-challenge/