Online scholarly catalogues: Data and insights from OSCI

Laura Mann, Frankly, Green + Webb USA, USA

Abstract

In 2009, the Getty Foundation launched the Online Scholarly Catalogue Initiative (OSCI; http://www.getty.edu/foundation/initiatives/current/osci/index.html), a landmark initiative to help museums make the transition from printed volumes to online publications. The OSCI initiative was completed in 2015, and the eight museums of the OSCI consortium have produced a diverse body of online scholarly catalogues (select catalogues are listed at http://www.getty.edu/foundation/initiatives/current/osci/osci_browse_catalogues.html). Importantly, we also now have an initial understanding of the reach and impact of these new publications. The Walker Art Center and San Francisco Museum of Modern Art have completed formal evaluations of their OSCI projects, which provide a rich body of evidence about how the catalogues are actually being used. The paper will explore the reach and impact of online scholarly publications and provide data and insights framed for the museum community at large: • Who is using online scholarly catalogues? • How are the catalogues being used? • What does the Web environment offer that makes online catalogues more useful? • How are the catalogues perceived by the target audience of scholars, art historians, and curators? • What are the drivers and barriers to the success of online scholarly publications? The research findings underscore the enormous potential for online scholarly publications, and even the opportunity for online catalogues to support new forms of scholarship and unique intersections between the museums and academic community. But they also reveal practical barriers to success and larger concerns around issues of permanence and status that are relevant to all museums exploring digital publishing.Keywords: digital publishing, online scholarly catalogues, museum publishing

1. Introduction

Publishing scholarly collections information is central to a museum’s mission, and print catalogues have historically been the keystone of museum publishing programs. But print catalogues have significant limitations: they are costly to produce and may be only available in research libraries, limiting their accessibility. They lack support for multimedia content and are difficult to update, which can limit their relevance.

In 2009, the Getty Foundation launched the Online Scholarly Catalogue Initiative (OSCI), a landmark program to help museums make the transition from printed volumes to online publications. The OSCI initiative concluded in 2015, and the eight museums of the OSCI consortium have produced a diverse body of online scholarly catalogues.

Nik Honeysett (2011) argues that the transition to online catalogues represents a major paradigm shift for museum publishing. Transitioning to the online environment is not simply a matter of substituting screen for printed page; rather, the shift requires us to rethink internal roles and production processes, and to consider how digital publications will be used and perceived by their target audience of scholars. The conclusion of the OSCI initiative presents an opportunity to reexamine the promise and reality of online scholarly publishing with the benefit of data from two OSCI projects.

Previous publications address how OSCI partners have approached the production and workflow challenges of online catalogues (Honeysett, 2011; Quigley & Neely, 2011; Neely & Quigley, 2012; Yiu, 2015). This paper will focus on the reach and impact of these new publications based on evaluations of the OSCI projects at the Walker Art Center and San Francisco Museum of Modern Art (SFMOMA). The evaluation findings provide insights into questions relevant to all museums exploring digital publishing:

- Who is using online scholarly catalogues?

- How are the catalogues being used?

- What does digital offer that makes online catalogues more useful?

- How are the catalogues perceived by the target audience of scholars, art historians, and curators?

- What are the drivers and barriers to the success of online scholarly publications?

2. Evaluation methodology

In 2014 and 2015, Frankly, Green + Webb evaluated SFMOMA’s Rauschenberg Research Project and the first two volumes of the Walker Art Center’s Living Collections Catalogue, On Performativity and Art Expanded, 1958–1978.

The evaluations used a wide range of methodologies, both quantitative and qualitative:

- Online surveys (SFMOMA n=350, Walker Art Center n=380)

- Google Analytics analysis

- User interviews

- Usability testing

- Museum stakeholder interviews

We interviewed and conducted usability testing with curators, professors, graduate students, and art librarians. We spoke with people who had previously used the catalogues for research and curatorial work and those who were seeing the publications for the first time.

3. Audience: Who is using online scholarly catalogues?

Our research showed that the target audience of scholars is using the online scholarly catalogues. Of survey respondents who had visited the Rauschenberg Research Project (RRP), 69 percent were from the primary audience of graduate students, professors, curators, independent scholars, and art librarians. The art historical profession has been slow to adopt online tools and digital publications, and this gives us some evidence that academic audiences will use online scholarly catalogues. The catalogues are also reaching a wider audience, including museum educators and artists.

Use of the catalogues is also broader and more diverse than that of a comparable print catalogue. In the six months after launch, the RRP and the Walker’s On Performativity had an average of more than sixteen thousand unique visitors (at the time of the evaluation, comparable data wasn’t yet available for the Walker’s Art Expanded, 1958–1978), much higher than the standard print run of a comparable print catalogue of the permanent collection. Even more significant is the geographic and institutional diversity of the online traffic: catalogue visitors came from an average of five hundred museum, university, and library network domains from around the world. An extraordinary 55 percent of visitors to On Performativity came from outside the United States.

We know that scholars are using the online catalogues. However, the data also suggest that there is significant potential for expanding the reach of the catalogues, especially among art historians at research universities and art librarians. Only 28 percent of the scholars who responded to the survey had heard of the Living Collections Catalogue (LLC) prior to seeing the invitation to complete the survey.

The data also show that users may need to hear about an online scholarly catalogue more than once before they visit. Of the primary audiences we surveyed who were aware of the RRP but had not previously visited, 74 percent said that they had “Planned to visit/Just not had time.” This suggests that there is significant potential for additional visitation. Scholars are eager to learn about new online resources, but multiple contacts may be necessary to generate a visit.

Communications strategies for scholarly publications should reflect the needs of the academic audience. Our research found that in generating awareness of the RRP and LCC, personal recommendations from known and trusted sources were most important. E-mails from the museum or related professional organization were the top sources of awareness. Of survey respondents from the primary audience, 23 percent learned of the RRP from a colleague or friend, suggesting that targeted e-mail communications to a small group of prominent scholars may be the best way to build awareness. Social media channels were far less important to the scholarly audience—only 1 percent of the primary audience for the RRP or LCC had learned of the catalogue from Twitter.

Maximizing the reach of online scholarly catalogues will require an outreach strategy and an ongoing communications program. This is one way that online scholarly catalogues represent a clear paradigm shift from print catalogues. Online catalogues may be more accessible, but they are also less visible to scholars who are accustomed to working with printed volumes. The updatability of online publications also means that online catalogues should be promoted on an ongoing basis, whenever there is new or updated content or features. This is a very different promotional model than the one-time publication announcement of a new print catalogue.

I would like an email from [the museum] every time a new module is loaded or a new volume published—I wouldn’t consider it a bother, I want to know when new, original content is being published. —Art librarian

Promoting online scholarly publications requires human and financial resources that should be factored into online catalogue budgets or publishing programs. Current museum publication workflows don’t support a model of an ongoing communications program for online catalogues. Moreover, there isn’t an established role in museums that is responsible for the marketing and promotion of online catalogues. Promoting publications to a specialist academic audience may be outside the wheelhouse of the marketing department, and the digital team may lack staff, financial resources, and expertise in promoting publications. Just as production of online scholarly catalogues requires new roles in museums, the promotion and marketing of online scholarly catalogues may not be an obvious fit for either a museum’s marketing or digital departments.

Discoverability: How do visitors find the online catalogues?

Google is the key to the discoverability of online scholarly catalogues; it is by far the greatest source of traffic to the RRP and LCC. More than 45 percent of all traffic, on average, comes to the catalogues through Google. Visitors came to the catalogues through general topic searches:

I was researching German pop art of the 1960’s and I found a [Google] link to Maja Wismer’s article in Volume II [of the LCC]. —Professor

Visitors also come through searches for specific facts:

I’m Googling for … some random fact about Rauschenberg in 1953 … and I often find that that takes me back to an essay in the RRP. —Graduate student

For other museums considering developing online scholarly catalogues, the role of Google in the discoverability of the publications underscores the importance of search engine optimization (SEO) and good metadata in particular.

Online catalogues may be more discoverable through Google than on your own site. The RRP is very tightly integrated into SFMOMA’s existing online collections pages on Rauschenberg, making the catalogue particularly SEO friendly. While the RRP is particularly findable through Google, it’s actually fairly hard to find on the SFMOMA site. Both analytics data and user testing show that RRP visitors who come through the SFMOMA home page have trouble finding the RRP and often resort to using site search to find the publication.

While most catalogue traffic comes through Google, the museum website does play an important role in discoverability. Scholars who are already familiar with a museum’s collection may go directly to its website for collections information.

I consult museum collection sites quite often like Tate and MOMA … I would use the [museum website] as well and would [expect to] find [the catalogue] there. —Professor

Ensuring that online catalogues are well integrated into collections records and site search is critical to maximizing findability by audiences that are already consulting the museum’s site.

Where do scholars expect to find an online catalogue?

Beyond Google, if online scholarly catalogues are to become part of the academic ecosystem, they need to be listed in the research databases that scholars use. The RRP and LCC are listed in key academic databases such as WorldCat and ProQuest, but the professors, curators, and graduate students we spoke to didn’t expect to find them there. Instead, scholars expect to find online scholarly catalogues in their university library catalogue.

How might these catalogues be listed in a library search? My starting point for research is still to go to my university’s library catalogue. —Graduate student

It’s parallel to a huge book … I might expect to see to it listed instead in the actual [university] library where they’re cataloguing books. —Graduate student

University libraries do catalog digital publications, but there is no standardized process for learning about or adding digital publications to library catalogs. Cataloging often depends on the art librarian seeing an e-mail from ARLIS or receiving a specific request from a professor; there are no standard channels of the kind that exist for print publications.

Online catalogs like these are a challenge to find out about and list in our local catalogs. A lot of that process is automated now for exhibition catalogs. These digital publications fall outside that normal stream. —Art librarian

Art librarians and visual resource center staff are key audiences for online scholarly publications. However, their needs are different than those of researchers. Obtaining an ISBN number for your online catalogue and creating readily available MARC records to add to library catalogs will streamline the process for art librarians. Librarians may need additional support to navigate new types of digital publications and assess whether to add an online scholarly publication to their library catalog.

4. How are online scholarly catalogues being used?

Online catalogue visitors to the RRP and LCC spend more time, view more pages, and return more frequently than general visitors to the sfmoma.org and walker.org websites. This is what we would expect to see from online scholarly publications.

Greater number of pages/visit

- Walkerart.org 2.39

- On Performativity 5.23

- Art Expanded 6.04

Longer time on site (minutes/session)

- Walkerart.org 1:37

- On Performativity 3:41

- Art Expanded 4:31

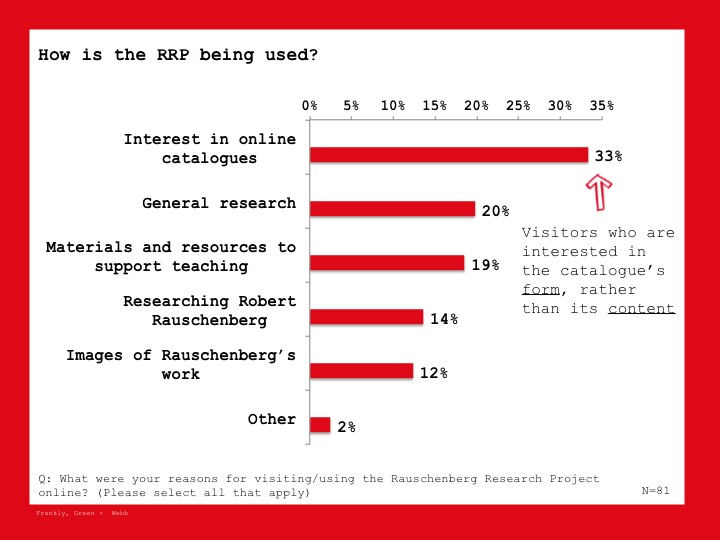

Digging a little deeper, we can see that scholars are using the catalogues for general and specific research, teaching, and locating images. A significant number of users are also visiting the catalogues out of an interest in the form of the online catalogue, rather than the content.

There was near universal praise for the usefulness, quality, depth, and breadth of RRP and LCC content.

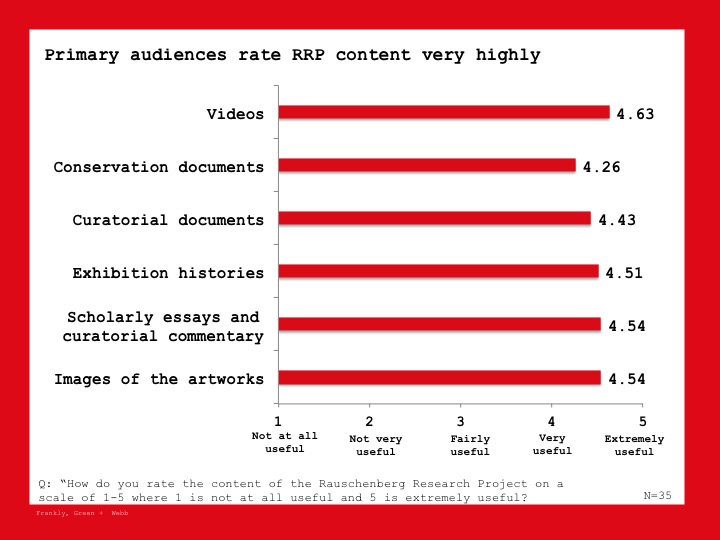

Scholars rated different types of catalogue content—from curatorial essays to videos—as very useful or extremely useful. And 98 percent of the primary audience said they were likely to use the RRP for future research on Robert Rauschenberg. These results are especially significant given that curators and academic art historians can be a critical, difficult-to-please audience.

5. What content and features matter most to scholarly users?

Scholars identified the quality and quantity of high-resolution images and multimedia support as two of the greatest strengths of the online format. This was particularly true for time-based artworks or artworks that can be played or operated. In this case, an online catalogue is uniquely suited to provide access to the art works. Users appreciated the multimedia integrated into the RRP and LCC, and they were disappointed by its absence. Expectations for online scholarly catalogues are different than those for print. The scholarly audience is aware of the capabilities of the digital format and expects a publication like this to exploit them.

Scholars also noticed and appreciated that high-quality images from the LCC are available through Google image searches, which supports use of the images and provides another path to discover the catalogue.

The Walker has made this move toward being more generously part of the image economy of the web. Seeing that the Walker was placing its bet on that public strategy I thought was really great. These images, if you’re doing Google image searches … will come up and so it’s possible to encounter the images loose from the frame of the Museum but of course they lead back. —Professor

Beyond artwork images and media, scholars were surprised and delighted that the catalogues provided access to information that is not usually available outside the museum, such as marks and inscriptions, exhibition and ownership histories, related correspondence and ephemera, conservation reports, and images of the backs of the paintings.

Allowing scholars access to all of the “extras” is amazing … curatorial and conservation documents, interviews, multiple views … personal photos, etc. Perhaps the most useful aspect … is … that users can download these resources to their own computers. —Independent scholar

This reminds us that downloadability is a key element in academic research workflow. Scholars consume scholarly essays online as PDFs and on paper depending on their needs.

If the article is critical for my research and teaching, I download it and print it, if it is useful but not essential, I download it. If I’m just giving it a cursory read, I will read it online. —Professor

Online catalogues need to support all of these modes of interaction. Downloadability also supports teaching workflow. University professors were enthusiastic about using the RRP and LCC for teaching, and the availability of downloadable PDFs will allow them to easily include a catalogue essay in a course e-reader. The presence of visible “download” buttons encourages downloading catalogue content and reduces friction for the user. Professors also want to be able to embed catalogue media directly in their PowerPoint lecture slides. Making it easy for faculty to use online scholarly catalogues with the tools they already use for teaching will encourage additional use in the classroom.

The RRP and LCC include content and features specifically designed for the scholarly audience, such as a citation tool that allows users to copy a properly formatted citation to their clipboards. The citation tool isn’t always used, but it is deeply appreciated. It signifies to the academic audience that the museum is considering their needs and that the catalogue is intended for citation. A recommended format for citation also reinforces the catalogue’s status as a legitimate scholarly source, which was especially important for professors looking for models of online scholarship for their undergraduate students.

[Recommended format for citation is] super super important … in terms of training our students in research and documentation. —Professor

Beyond individual site features, scholarly audiences identified how the catalogues break new ground for online museum content and propose new forms for the museum publication. Scholars saw a distinctive curatorial voice and vision in the LCC:

There can be a tendency on the web for museums to strike a kind of neutral, very bland quasi-bureaucratic tone when they talk about their work. – I felt like these texts had a lot of personality to them more so than you usually see in a museum frame and a kind of independent scholarly seriousness that I appreciated. —Professor

Scholars also saw the LCC as offering a model for an online scholarly catalogue in which original thematic essays by prominent scholars establish authority and status for the volumes, while archival materials provide building blocks to spur new research.

Academic users described the RRP as a new type of publication that combines elements from print catalogues, collections websites, and internal museum files into something genuinely new and valuable.

The … content of the essays was … the most surprising and interesting thing for me. The essays by SFMOMA curators had insights about the physical objects, their histories, that don’t appear in traditional art historical scholarship written by people who have limited access to the objects … The RRP appears to be a new kind of thing … a unique publication … It’s a new kind of form. —Graduate student

At their best, online publications have the potential to meet the needs of the scholarly audience in new ways, with the online environment supporting innovation in content and form. Future online scholarly catalogues can build on the strengths of the RRP and LCC, creating something new rather than seeking to emulate existing academic models.

6. What are the user experience challenges for online catalogues?

We have seen that online scholarly publications have enormous potential, but the shift to the online environment also poses some real usability challenges for the users and designers of these publications.

Our research highlights that the user journey with an online publication is different than that of a printed publication. The majority of visitors do not enter the catalogue through the home page: 70 percent of LCC visitors and 79 percent of RRP visitors enter the catalogues through a specific essay or a specific artwork.

[A colleague] sent me a link directly to the essay. I wasn’t exactly sure what it was … It’s a nice new take and it’s very ambitious but that’s why it took some time for me to figure out what I was looking at. —Curator

Many visitors to an online catalogue will never see the introductory paragraph on the home page or the table of contents. This poses usability challenges, as users struggle to orient themselves within the publication. Understanding the user journey with an online catalogue will enable us to design for user needs and the realities of the user experience.

Users of the LCC and RRP also struggled to understand the scope of the catalogues.

As a traditional art historian who likes to know upfront what I’m getting into, I’d also like an alternative, more straightforward scope statement about what the catalogues covered … something explicit about what the catalogue provides (how many essays, etc.), rather than just allowing visitors to explore (i.e. bumble). —Art librarian

I was disappointed that it didn’t have a little map of the structure of the thing … or at least a list of here are the basic sections and the essays. —Graduate student

We quickly judge the scope of a printed catalogue by feeling the heft of the book and scanning the table of contents and list of artworks, but online publications do not reveal themselves so easily. Scholars need to quickly understand the contents and scale of the catalogue: how many essays? Artworks? Artists? Capturing the scale of an online publication is also important when communicating with internal museum stakeholders to secure human and financial resources for online catalogue projects. How might we design for these needs?

Understanding the contents and scale of the catalogue is a particular challenge with archival materials. As mentioned above, the RRP and LCC both include extensive archival materials, and these materials are linked to individual objects or appear within essays. Tying archival materials to object entries makes them far less visible and limits the usefulness of the materials for the scholarly audience. In usability testing, users found it relatively easy to locate the materials when they were researching specific objects, but finding exhibition brochures, correspondence, or installation photos without knowing which artworks they were associated with was much more challenging, if not impossible.

Scholars want flexible tools for browsing and search catalogue content. If the catalogue is organized around thematic essays, is there a separate list of all of the artworks referenced in the catalogue? Can users browse and search all the primary source/archival materials without needing to consult each object record? Academic users will want to use online scholarly catalogues in ways we haven’t anticipated, and this challenges us to design publications that are flexible enough to allow scholars to mine our content in new ways.

7. How does the academic audience perceive online scholarly catalogues?

Scholars are enthusiastic about digital resources and can clearly articulate advantages of an online scholarly catalogue. The target academic audience saw several key advantages to the online format:

- Accessibility

- Searchability

- Updatability

- Multimedia content

Scholars see the RRP and LCC as trustworthy and legitimate scholarly sources for both citation and publication.

- Of the primary audience (curators, professors, independent scholars, graduate students, art librarians), 78 percent said that they were either very likely or extremely likely to use the LCC for future research on performance art or the art of 1958 to 1978

- Of the primary audience who had used the LCC, 85 percent rated it as either a very credible or extremely credible place to have their own work published

- Of the primary audience that had used the LCC (N=40), 30 percent indicated that they were very likely or extremely likely to cite the LCC in future research or publications

The willingness to use, contribute to, and cite the catalogues stands in stark contrast to the overall perception among scholars of a lack of rigor in online publications.

Generally … I don’t cite online material … but because of the rigor that was used in this project, I felt comfortable citing it. —Graduate student

It is refreshing to see a publication that is intentionally anchoring itself for use by scholars. I have hesitated to publish scholarship online, in fear that my work would be seen as ‘just popular,’ but I would be proud to have an article in an online journal/catalog like this one. —Professor

Why do scholars trust these two publications? For the target audience, the signifiers of authority are:

- Institutional brand (SFMOMA, Walker, Getty)

- Prominent contributors

- Academic format and proper citations

- Visual design

What comes across … is less “online catalogue” which isn’t … prestigious and more “the Walker” which is an institution that does have a lot of respect in the field. —Professor

I would also evaluate it based on what I know of the reputation of the individuals involved. —Professor

There are very good people … I know the people and I know their work. I don’t care too much about peer review. —Professor

Perception of the catalogues is shaped more by the reputation of the contributors than by the presence or absence of peer review. This would suggest that museums working on online scholarly catalogues should invest their resources in securing prominent senior scholars as contributors rather than having their content peer reviewed.

One measure of success for online scholarly catalogues is their impact on new scholarship. The full impact of the catalogues will not be visible for many years, but we do know that the availability of sources through the LCC and RRP have already had a direct effect on academic scholarship.

I am writing my dissertation on the work of Allan Kaprow, and although I wasn’t planning to write about Mushroom, I will, since the photographs and especially the letters [in On Performativity] enable me to deal with the happening in a nuanced, substantial way. —Graduate student

The [catalogue] was a huge asset for [my Masters] paper … I actually held off on finishing my paper so I would have access to the information on the RRP website. —Graduate student

8. What are the barriers to the success of online scholarly catalogues?

The scholarly audience clearly saw the benefits of online scholarly publications, and they valued and trusted the RRP and LCC. But our research also points to some of the challenges to this type of digital publishing. Some challenges are specific to online publications and to museums, but others reflect larger issues in the academic world.

Boundaries: where does the publication begin and end?

The LCC and RRP both propose the online catalogue as a new form that blends elements from print catalogues and magazines, online collections, and digital publications. The RRP, in particular, is highly integrated into SFMOMA’s online collections pages; it doesn’t resemble a book in digital form. Users viewed this approach positively, and it translated into a highly replicable technical architecture for the museum. The downside of this tight integration is that users had trouble identifying the boundaries of the publication, and that was a significant concern for academic users.

Where is the container that makes this into a separate publication? Does it bleed out into the rest of the website? … where does the publication begin and where does it end? And how do you tell when you’re in it or not in it? —Graduate student

Users were, for example, reluctant to use the general search box out of concern that it would yield results from outside the RRP. This is partially an issue of expectations: some users expected the RRP to look more like a separate publication. But before we chalk this up to users just being old fashioned, we should remember that RRP content reflects a level of academic rigor that distinguishes it from other site content. Confusion about the boundaries of the RRP has the potential to undermine audience trust in the publication as a specialist, scholarly source.

Permanence: will this be here in twenty years?

Permanence is an enormous concern for the scholarly audience. It’s a concern for those citing online publications and those contributing to them.

If you cite something there’s the possibility that it would disappear. There’s a lot of scholarly nervousness about that. —Graduate student

20 years from now, will we be able to read this data? … If it’s in a library catalogue … will that URL be stable? —Graduate student

Scholars appreciated the LCC’s explicit assurance of a permanent address for the catalogue, but this was tempered by negative experiences with broken links in citations to online sources.

As enthusiastic as I am … about the future of electronic publications, their lack of durability is very frightening for any institution that is essentially in … the memory business. —Professor

Academic audiences value the updatability of digital publications tremendously, but they don’t want to lose the record of the original object. The updatability of online catalogues is seen as a huge advantage, but there is still great value placed on retaining the original published source as an object. One interviewee observed that “the publications themselves communicate things to the future.” Versioning editions of an online scholarly catalogue are part of the solution. More broadly, how might online scholarly catalogues be permanent, updatable, and archival? This is a challenge that digital scholarly publications need to address so it does not undermine the perception of the usefulness of digital.

Status: what counts for tenure?

Scholars told us that the RRP and LCC had a real impact on their view of online scholarly catalogues. The RRP and LCC have changed more than a few minds in the scholarly community about the legitimacy and possibilities for online publishing.

It changed my opinion … it served for me as an example of what’s possible. —Graduate student

I saw that one could be done in a very comprehensive and scholarly manner. I’m not sure I was a big believer prior to that. —Curator and RRP contributor

Academics were enthusiastic about writing for online catalogues like the RRP and LCC. But for scholars in university tenure-track positions, this was tempered by the concern that museum publications—both print and digital—don’t count towards the academic tenure file.

Researchers, writers, students prefer the ease of access to online sources. However, funders, reviewers and institutional review boards (grant panels, tenure committees) do not seem to value online contributions as they do printed books. —Professor

I have published in museum publications before. And … what I’ve been told is that they don’t count towards tenure review…they…aren’t considered tenure-worthy. But … the RRP that’s some new territory I think… —Graduate student

Scholars acknowledged that the tenure process is evolving, but for now perceptions of online scholarly catalogues will continue to be shaped by larger issues of status and publication record in the academic community.

9. Conclusion

The research findings from our evaluations of the Living Collections Catalogue and the Rauschenberg Research Project underscore the enormous potential for online scholarly publications, and even the opportunity for online catalogues to support new forms of scholarship and unique intersections between the museums and academic community. But they also reveal practical barriers to success and larger concerns around issues of permanence and status that are relevant to all museums exploring digital publishing.

Acknowledgements

I’m grateful to the staff at Walker Art Center and SFMOMA for their many contributions to the evaluation projects.

References

Honeysett, N. (2011). “The Transition to Online Scholarly Catalogues.” In J. Trant and D. Bearman (eds.). Museums and the Web 2011: Proceedings. Toronto: Archives & Museum Informatics. Published March 31, 2011. Consulted September 30, 2015. Available http://www.museumsandtheweb.com/mw2011/papers/transition_to_online_scholarly_catalogues

Neely, E., & S. Quigley. (2012). “Online Scholarly Catalogues at the Art Institute of Chicago: From Planning to Implementation.” In J. Trant and D. Bearman (eds.). Museums and the Web 2012: Proceedings. Toronto: Archives & Museum Informatics. Published April 6, 2012. Consulted September 30, 2015. Available http://www.museumsandtheweb.com/mw2012/papers/online_scholarly_catalogues_at_the_art_institu.html

Quigley, S., & E. Neely. (2011). “Integration of Print and Digital Publishing Workflows at the Art Institute of Chicago.” In J. Trant and D. Bearman (eds.). Museums and the Web 2011: Proceedings. Toronto: Archives & Museum Informatics. Published March 31, 2011. Consulted September 30, 2015. Available http://www.museumsandtheweb.com/mw2011/papers/integration_of_print_and_digital_publishing_wo.html

Yiu., A. (2013). “New Norm for Studying Chinese Painting and Calligraphy Online.” In N. Proctor & R. Cherry (eds.). Silver Spring, MD: Museums and the Web. Published October 11, 2013. Consulted September 30, 2015. Available http://mwa2013.museumsandtheweb.com/paper/a-new-norm-for-studying-chinese-painting-and-calligraphy-online/

Cite as:

Mann, Laura. "Online scholarly catalogues: Data and insights from OSCI." MW2016: Museums and the Web 2016. Published March 21, 2016. Consulted .

https://mw2016.museumsandtheweb.com/paper/online-scholarly-catalogues-data-and-insights-from-osci/