Digital collection content creation at the DMA

Shyam Oberoi, Royal Ontario Museum (ROM), Canada, Andrea Severin Goins, Dallas Museum of Art, USA

Abstract

As part of a grant-funded project that began in September 2013, the Dallas Museum of Art (DMA) is digitizing its collection of over twenty-three thousand artworks as a two-part initiative. High-resolution photography of artwork not previously photographed and establishing the technical framework to publish this content constitute the first part. The second involves extensive cataloging of these works; the digitization of rich, supplementary contextual content for those works; and developing technical processes to route content internally, link content to both existing internal digital resources and external taxonomies, and harvest content for publication online via a collections API. Examples of this supplementary digital content include artist and designer biographies; catalogue essays; cultural and geographical descriptions; definitions of materials, processes, and art historical terms; smartphone assets, program recordings, and other multimedia assets; contextual images; related Web resources; and teacher resources. This paper and presentation will overview the challenges, iterations, and successes related to the management of the project from the technical, administrative, and interpretive perspectives. Reflecting on the trials and errors of our process thus far, this presentation and paper will strive to illuminate effective, interdepartmental strategies to rendering extensive object research accessible and easily navigable to online visitors. Additionally, we will provide insight into both the interpretive and technical approaches to creating rich connections between a vast and broad collection through associations with thematic content.Keywords: Online Collections, digitization workflows, data architecture, educational content, contextual information

1. Introduction

In September 2013, the Dallas Museum of Art (DMA) received a gift that provided the necessary means to digitize its collection of over 23,000 artworks and allow open access to physical and virtual visitors. The ongoing grant-funded project is a two-part initiative. High-resolution photography of artwork not previously photographed (around 14,700 objects) constitutes the first part. The second part, which will be explicated in this paper, involves extensive cataloging of on-view and recently on-view artworks—roughly 5,000 works of art—and the digitization of rich, supplemental contextual content for those works. This supplemental content includes artist biographies; catalogue essays; cultural and geographical descriptions; definitions of materials, processes, and art historical terms; audio-guide tour stops, program recordings, and other multimedia assets; contextual images; related Web resources; and teacher resources.

In preparation for this work, the DMA hired a team of four new staff, or digital collections content coordinators (D3Cs), each with specific academic backgrounds and expertise that reflect the diverse areas of the Museum’s collection. While their backgrounds are primarily art historical, their work reflects a strong understanding of audience needs and accessibility. Their primary role is essentially twofold: first, to aggregate, create, and digitize content; and second, to associate that content with works of art in the Museum’s collection. For content creation, the D3Cs search first among DMA materials, many of which don’t exist in easily searchable digital form—the paper object file and record, DMA publications, exhibition catalogues, label text, gallery didactics, teaching materials, and internal files. Searches for supplemental content then extend to other external digital sources. In a unique interdepartmental collaboration across technology, education, curatorial, registration, and the library, we have streamlined a process for researching, digitizing, organizing, associating, tagging, and exporting diverse supplemental content for the eventual online collection. One year into the project, we have prepared nearly two thousand units of associated content. This paper will provide an overview of the management of the project from the administrative, interpretive, and technical perspectives. In doing so, we will strive to illuminate an effective, interdepartmental model for rendering extensive object research accessible and easily navigable to online visitors.

2. Evernote

Among the project’s first challenges was the selection of a suitable software tool for the storage and organization of the myriad types of content the D3Cs would be examining. Our existing databases—The Museum System (TMS) for collection information and Piction for digital asset management—were not appropriate: TMS does not allow for the complex formatting nor the integration of text, images, and hyperlinks that we envisioned as part of this project; much of the content we planned to create would be primarily text-based and would need to be easily editable, which precluded Piction. After some deliberation and research, we chose Evernote Business as the primary platform for creating, storing, and organizing this newly generated supplemental content. As we planned for a large amount of content in a variety of formats (text, video, audio, image) to be edited and shared across multiple stakeholders, the following features of Evernote appealed to us:

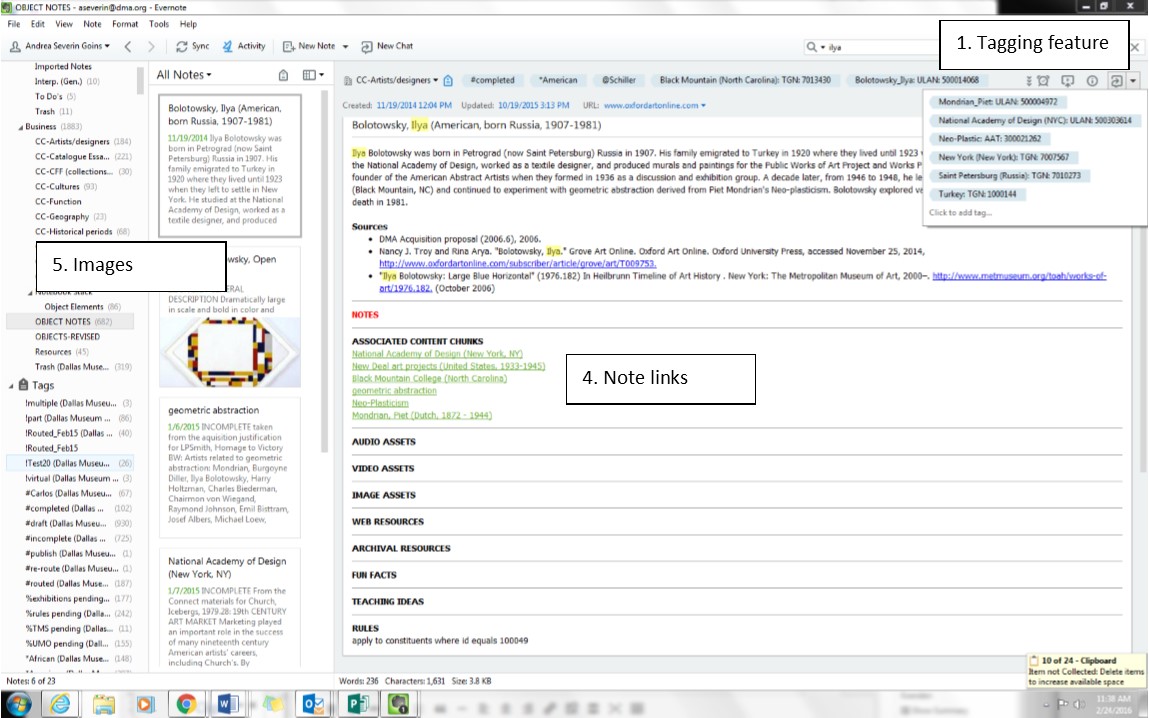

- The tagging feature: while Evernote content (referred to as “notes”) can be organized into “notebooks” and, further, into “notebook stacks,” the flexibility of organizing and categorizing content through tagging is probably Evernote’s most useful feature. Tags created by one team member are visible and usable to all team members. This means that tags can associate artworks and content chunks authored by different users, and consequently across different collections.

- The ease of sharing content: Evernote automatically syncs new or edited content across all team members’ devices. Team members can access and edit content via the desktop client, their phones, iPads, or the Web-based application on any device.

- The ease of searching across a large amount of content: the Evernote search function covers all text, including attached Word docs and PDFs.

- The ability to link content within Evernote as hyperlinks: before determining a process to associate artworks with supplemental content, this feature appeared useful for creating these connections. Though we now associate content and artworks with a rules engine (See Section VII), we continue to use note links to associate supplemental content thematically to other pieces of supplemental content.

- The ability to hold content in a variety of formats: Evernote stores documents, PDFs, images, hyperlinks to Web resources, and multimedia content. PDFs can also be annotated within Evernote.

- Evernote API: this allows us to easily harvest any content recorded in Evernote and integrate it with the rest of the DMA’s collection information sources.

Evernote, like all software, is not without its issues: the service can be accessed via browser, desktop client, or app, and all are subject to program crashes, inconsistency with content synchronization, and various bugs (the software is updated frequently). Nevertheless, one year into this project we still feel comfortable with our choice of platform that, if nothing else, has freed the DMA from a lengthy and complicated software development process.

3. TMS and the digitization project

As mentioned, we determined that TMS would not be an appropriate repository for some of the supplemental and contextual content we intended to gather and digitize. However, TMS is used on a daily basis for the project. First, the team confirms each artwork’s metadata and cross-references with current scholarship, which they have compiled. They pay particular attention to the core tombstone metadata fields in TMS that are already harvested for the DMA’s online collection.

In order to render our collection data more searchable and dynamic, as part of this project team members are adding geographical information that references the Getty Thesaurus of Geographic Names (TGN) to TMS. For each artwork they complete, they enter in the Geography XRefs field the TGN unique identifier and the “type” or relationship of that geographic place to the artwork. As we will see, the Getty Vocabularies and other Linked Open Data data sets are critical to this project.

The D3Cs are also ensuring that the artworks they cover are appropriately associated with exhibitions recorded in TMS’s exhibition history module. Working closely with the DMA archivist, when necessary, the D3Cs at times add past exhibitions to the module before associating related artworks with it.

4. Developing an information architecture

Our second challenge involved development of an information architecture—a framework for organizing a large amount of content—diverse in its format, source, and type consistently across our diverse collections. A number of interdepartmental brainstorm sessions resulted in the formalization of supplemental content types. It was necessary for these types or categories to be capable of universal description—able to capture contextual information about an encyclopedic collection. Broadly, supplemental content can be categorized in two ways: content that specifically relates to one artwork, and content that can be generally applied to multiple artworks.

Specific supplemental content includes the following:

- General descriptions

- Related objects

- Provenance

- Multimedia assets

- Links to external Web resources

- Archival resources

- Teaching resources

- “Fun facts”

General supplemental content is organized into the following categories:

- Catalogue essays

- Artist/designers

- Culture

- Geography

- Process/materials

- Historical periods

- Individuals

- Terms

The results are formalized templates within Evernote, which are necessary in order to ensure that the information captured by the D3Cs can be successfully and repeatably harvested into a resource we call the “Brain” (a framework to support a potentially endless amount of content aggregation, connectivity, and dissemination), and properly mapped to collection information in TMS and digital assets in Piction.

5. Designing a workflow

To determine monthly goals for the D3C team, we first divided up the roughly five thousand artworks to be covered as equally as possible across the four staff members based on their expertise.

Accounting for the total amount of time allotted to complete the project, and taking into account extra time for workflow and process refinement, we established clear and achievable quotas (twenty-five artworks per person per month) that ensures that our team will cover five thousand artworks in the four-year period denoted by the grant. However, we project that the actual number of artworks covered will be significantly greater; as the D3C’s “pool” of generated content grows, the general time required to cover an artwork will decrease (since the content will have already been created).

Step 1: Creating an Evernote note for each artwork to be completed

Each piece of content—or page—created in Evernote constitutes a “note.” At the beginning of each month, each D3C indicates in a shared note which group of artworks he/she will complete during that month. To complete an object, the D3Cs create a new note for that artwork. Each artwork note consists of a predesigned form with fields for the specific and general supplemental content categories listed in Section IV. (see Appendix A for descriptions of each of these categories) A field for internal notes or questions is also included on each object template.

Specific supplemental content fields are primarily filled with text-based content. Every piece of written content is carefully cited. We developed a system to indicate the role of the material’s source, which is useful internally for content and copy edits, and will be useful for researchers visiting our future online collection. Excerpts from DMA publications are cited as “Excerpt from”; text that has undergone copy or syntactical edits is cited as “adapted from”; summarized content or content aggregated from multiple sources is cited as “drawn from.”

General supplemental content fields are filled with hyperlinks to “content chunks” (See Step. 2), which the D3Cs create—or have already created—during the object completion process. The D3Cs fill in these fields when applicable and when the content is readily accessible to them—either in a digitized format or in need of digitization.

Multimedia assets and Piction

The D3Cs search the DMA’s digital asset management software, Piction, and other resources for contextual images as well as audio and video content that references the specific work of art. Specific metadata fields within Piction were designated as part of this project as indicators of content for the online collection. When an asset is already stored within Piction, the associated artwork’s accession number is added to the metadata and a descriptive caption is confirmed or created. The content team actively searches for multimedia assets outside of Piction and uploads and catalogues them as needed.

Step 2: Creating “content chunks” (general supplemental content)

The second step involves generating content chunks, which refers to primarily text-based general supplemental content that could potentially be associated with multiple artworks (biographies, cultural descriptions, material definitions, etc.). An Evernote note is created for each content chunk. Each note follows a template with fields similar to the artwork template described in Step 1. (see Appendix B for content chunk template) Content chunks are organized in folders—called “notebooks in Evernote—that reflect the general supplemental content categories listed in Section IV.

Multimedia assets for content chunks: We currently use the tagging function within Evernote (described in Section VI) to associate content chunks with audio, video, or image assets stored in Piction.

Associating content chunks: Associations between artworks and content chunks are created via an internal rules engine (described in Section VII).

Step 3: Data harvest and export

Once these notes—content chunks as well and artworks—are completed in Evernote, they are harvested into the “Brain.” At its heart sits Django, a Python Web framework, with MongoDB, a document-oriented database, aka a schemaless or noSQL DB. While its technical implementation is specific to the DMA, the general approach is not: more and more museums are looking at flexible ways to bring together their previously siloed legacy dataset (for example, the Getty’s Digital Object Repository, or DOR (see Sissman, 2015)). Brain was already in place at the DMA prior to the D3C work, harvesting object information from TMS and the images associated with those objects in Piction. Given its flexible framework, and since each of Evernote’s “notes” referenced an object in the DMA’s collection that was already available in Brain, adding Evernote as an additional data source was relatively straightforward.

In order that this content can be reviewed, commented on, and edited by a wide range of other internal stakeholders, when a note is harvested into Brain it is also transformed into a Google Doc and placed in a shared drive (see section VIII).

6. Tagging and categorizing

In Evernote, the D3Cs developed a complex tagging system for creating categories and connections across all collections and applicable to both artworks and supplemental content. Tags will improve the search function of the online collection, and are useful for organization within Evernote. Each Evernote note—whether an artwork template or a “content chunk”—is tagged with a combination of two kinds of tags: 1) tags that indicate institutionally specific information, and 2) tags derived from the Getty vocabularies and other external taxonomies.

Institutionally specific tags

One of the most important institutionally specific tags associates an artwork note with the accession number of that artwork as it is recorded in TMS, our collection database. These tags are formatted as TMS: [Accession number]. This tag connects supplemental content stored in Evernote specific to an artwork with the “essential content”—the identifying content about that artwork stored in TMS.

Some institutionally specific tags indicate author (@[author last name]), collection (*[collection title]), and type of supplemental content—such as a glossary entry (.[type]). These tags function solely for internal record keeping and organization.

Other internal tags (#draft and #publish) designate the stage of completion of an artwork note or content chunk, and indicate when content is ready to be harvested in Brain (#draft) and subsequently routed for review via Google Docs (see Section VIII). The tag #publish indicates the content is ready to be visible on our online collection.

Multimedia assets for content chunks

We currently use the tagging function to associate content chunks with audio, video, or image assets stored in our multimedia database, Piction. When a content chunk is associated with an asset stored in Piction, we tag that content chunk with a tag formatted “UMO: [Piction I.D. of asset].”

Tags derived from the Getty vocabularies

“Getty tags” are terms found in one of the Getty Vocabularies: ULAN (Union List of Artist Names), AAT (Art & Architecture Thesaurus), and TGN (Thesaurus of Geographic Names). These vocabularies include structured terminology for art, architecture, decorative arts, etc. Each entry includes alternate spellings, linguistic variances, interchangeable terms, and maps relationships to other terms hierarchically. For example, in TGN the entry for “Dallas” is a subset of “Texas” and a further subset of the “United States.” The vocabularies expand with contributions and serve as an authority for catalogers, researchers, and data providers.

The Getty tags we use within Evernote are formatted as [term]: [AAT/TGN/ULAN]: [Getty unique identifier code]. These tags describe both objective and subjective information. Objective information includes artist names, medium, process, historical or artistic periods, and artwork types (installation, sculpture, lithograph, etc.). Subjective tags can be descriptive (shiny, scale, abstract, etc.) and include subject matter (human figures, guardian lions, funerary object, etc.). By referencing the Getty Vocabularies, we are able to build hierarchical connections and categories. For example, a search query for “Italy” on our online collection would return not only content chunks and artwork tagged “Italy: TGN: 1000080,” but also artwork and content chunks tagged with “Rome: TGN: 7003138.”

7. Dynamic and sustainable associations

Content chunks—the term we gave to primarily text-based general supplemental content—include biographies, cultural descriptions, material and artistic process definitions, explanations of historical or art historical periods, etc. In the middle of the first year of the project, it became apparent that many of these content chunks were highly relevant to more artworks in the DMA’s collection than the five thousand objects in the initial project scope. For example, a general overview of the Nasca peoples, an indigenous Peruvian culture, written for a specific highlight object in the DMA’s collection would also be useful for all other DMA objects from this same culture. With Evernote, we knew that we could manually tag these other objects, but that process would be laborious and static; as new objects entered the collection, or as scholarship changed, these linkages would become increasingly obsolete.

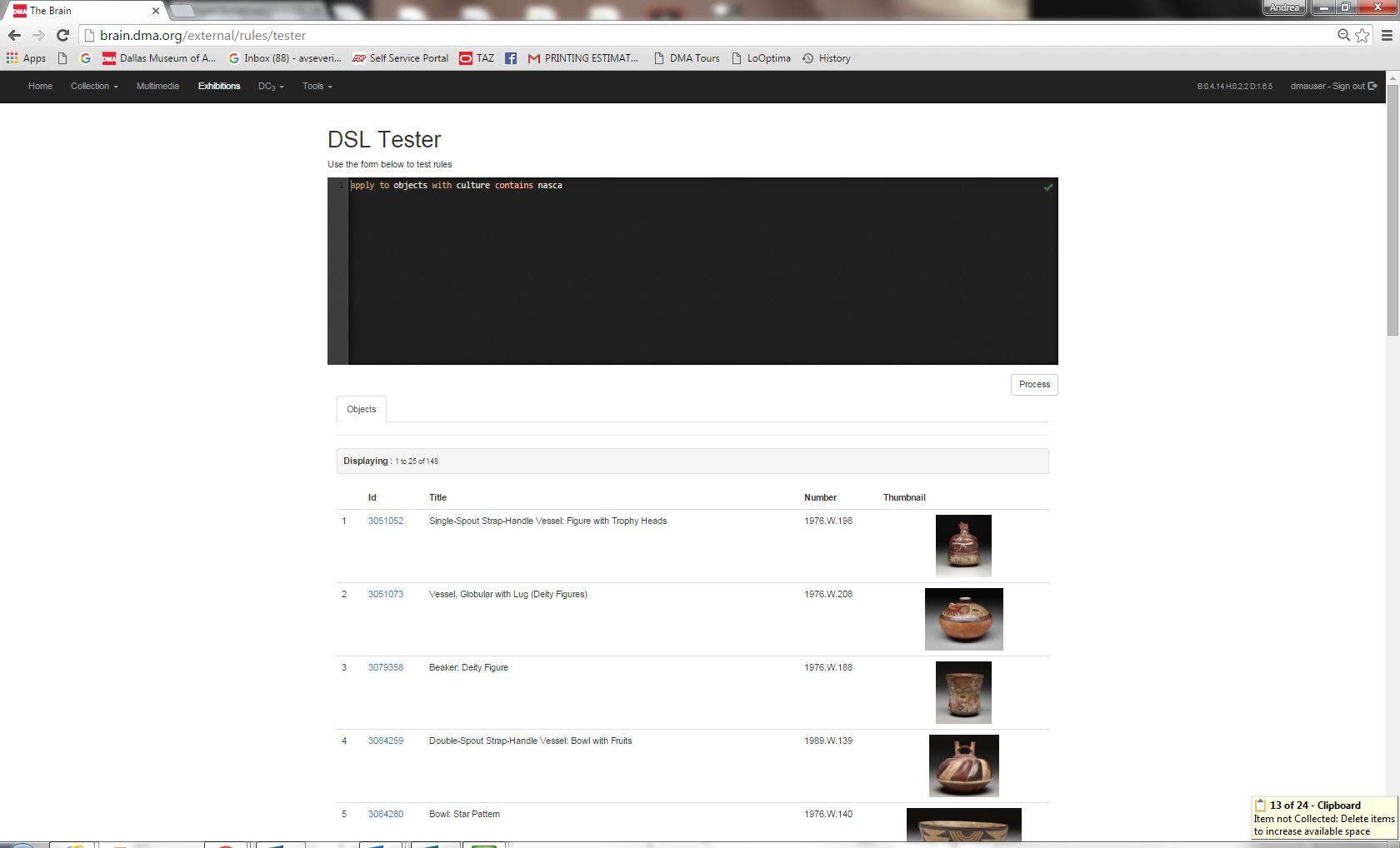

In order to dynamically associate these general content chunks broadly across the entire collection, we developed a rules engine based on Boolean logic and fed from existing object metadata. For each content chunk, a rule is written that describes which artworks within the collection that content chunk should be associated with. Most often, rules apply to objects; however, in cases like biographies, for example, content chunks may apply to constituents. Rules are formatted as “apply to [target] with [attribute] equals [value].” Targets, attributes, and values all refer to object metadata within TMS. Multiple conditions can exist as part of a single rule, allowing for additional complexity.

For example, we would want to associate a content chunk that describes the Nasca peoples with all artworks in our collection classified as belonging to the cultural group Nasca. The rule would look like: APPLY to OBJECTS with CULTURE contains NASCA. The result is 149 artworks in which “Nasca” is included in the cultures field within TMS. A rules tester was developed in “Brain” that validates and processes rules and displays the affected artworks. That way, we ensure the rule is appropriate and accurate before we assign the rule to a content chunk.

Each artwork note is also assigned a rule that creates a connection between that artwork-specific supplemental content and the artwork record, which is already harvested in Brain. Ultimately, this rules engine will ensure sustainability of the content, should scholarship change or in the event of acquisitions/de-acquisitions. As long as the metadata within TMS is maintained, associations to supplemental content sourced from Evernote will remain up to date.

8. Interdepartmental routing

While some of the supplemental content generated as part of this project is excerpted from recent DMA publications, other content is newly written or summarized and requires approval from the curatorial department, as well as copy editing. To streamline this process, we are using Google Docs with an add-on—Collavate—to manage the interdepartmental routing.

Once the D3C completes an artwork or a content chunk, he/she tags the note with an internal tag that indicates that the content can be harvested in Brain. Once harvested in Brain, notes are exported into Google Drive. Artwork content is exported into folders by collection (curatorial department), while general content chunks are stored in a separate folder. Curators overseeing a particular collection will receive an email notification when new content is added to their specific collection folder within the Drive. Once they edit and approve, our copy editor will review and approve. Once all necessary internal staff have reviewed the content chunk or artwork, the author of that content—the D3C—receives email notification. He/she makes any necessary edits to the content manually in Evernote and uses a separate tag to indicate that content is ready to be reharvested for publication online.

9. Next steps

One year into the project, the D3Cs have completed more than one thousand unique object notes and content chunks describing the DMA’s encyclopedic collection. We have demonstrated that we can both utilize existing commercial software (Evernote, Google Drive) for content cataloguing and workflow routing and integrate this work into the rest of our aggregated collection information (Brain). For us, the next step in the digital collections content project will be reimaging the DMA’s online collection user interface in order to accommodate the wealth and diversity of scholarly content uncovered by the D3Cs. We envision publishing this supplemental content on a rolling basis, in order to allow for testing and template iterations. The content generation portion of the project (five thousand works of art with extended content) and full publication online will be complete by the fall of 2018.

Reference

Sissman, Daniel. (2015). “A new DOR opens: How the J. Paul Getty Museum is reimagining digital collection information management.” In MW2015: Museums and the Web 2015.

Appendix A: Specific supplemental content

The following fields relate specifically to the artwork. Content within these fields is harvested in Brain.

General description: 150 to 300 words based on most up-to-date scholarship, a combination of the following resources: current label copy, catalogue entry, acquisition justification, etc.

Notes: Internal questions or comments.

Related objects: List of, when applicable, other artwork (that may or may not be in our collection) that is essential to the understanding of the artwork. For example, if the DMA artwork is a study for a painting, the painting will be listed here.

Provenance: Duplicated from the TMS database.*

* As part of this project, the D3Cs are reformatting provenance entries in TMS to follow a new institutional standard.

Audio assets: Audio, video, and image assets are fields that list and describe these assets. Content within these fields is for internal organization and record. Actual associations between multimedia assets and artworks are created through Piction (see Section V).

Video assets: See above.

Image assets: See above.

External Web resources: Text-based caption, along with a hyperlink to external source.

Archival resources: Description of potential archival resources for internal records; as part of the workflow, each month potential resources are compiled and sent to archivist for upload to Piction.

Fun facts: Miscellaneous content related to artwork.

Teaching ideas: Text-based teaching ideas pulled from online teaching materials or DMA educational resources.

Appendix B: General supplemental content

The following fields only include hyperlinks that indicate an associated content chunk. These links are harvested in Brain.

Catalogue essays: Digitized passages from DMA publications; often this is an elaboration of an artwork’s wall label or general description.

Artist/designers: Biographies.

Cultures: Descriptions of cultural groups or traditions.

Geography: Explanation of places; often historical.

Process/materials: Definitions and descriptions of artistic processes and materials.

Historical periods: General historical context.

Individuals: Biographies of individuals including deities; rulers; historic and mythological figures; religious figures; associated artists; and related persons (patrons, for example).

Terms: Definitions and descriptions of subject matter; art-related or culturally specific terminology ad concepts, including art historical styles and genres; or explanations of relevant art institutions or organizations.

Cite as:

Oberoi, Shyam and Andrea Severin Goins. "Digital collection content creation at the DMA." MW2016: Museums and the Web 2016. Published January 31, 2016. Consulted .

https://mw2016.museumsandtheweb.com/paper/digital-collection-content-creation-at-the-dma/